Optimize the Harvest

Key Action Area

Optimize the Harvest

Action Area

Optimize the Harvest

Summary

Of the nearly 15 million tons of surplus produce generated at the farm level, a staggering 82% reached maturity but was left behind after harvest. Some of this was considered inedible for reasons including rot and insect infestation (although it still could potentially be used for non-food purposes), but more than a quarter of the surplus was left behind, because it was considered “not marketable” – frequently because of overly strict quality or appearance standards established by stakeholders further down the supply chain. And surprisingly, another 22% of what was left behind was actually considered marketable, but it wasn’t harvested for other reasons, including insufficient labor to harvest, or because it was planned surplus for contracts that had already been fulfilled for the season or because the cost to harvest was greater than the selling price. This means that about half of the produce left on farm was perfectly edible.

"Optimizing the harvest" means aligning what is grown with what is ultimately harvested, by avoiding overproduction and then harvesting as much as possible. When it comes to wild-caught products, such as fish, some animals, and certain types of produce, it means sourcing only what is needed. Solutions in this action area include finding new ways to sell and donate what’s left after harvest, such as developing innovative contract structures that don’t incentivize overproduction, and improving systems of communication that relay forecasted demands back up the supply chain to producers. Additionally, technological innovations that streamline individual, cross-sector, and cross-supply chain data-sharing could amplify the benefits. While these solutions manifest in less waste at production, the opportunities and responsibility to implement them lie across all supply chain actors.

A majority of the investments needed for solution adoption in this action area come from Corporate Finance and Spending, where the companies and organizations that invest in development and implementation of the solutions will receive the greatest benefit. The next largest contribution is from Private Equity, indicating that there is a need for expansion capital for imperfect produce channels. An equal split between Impact-First Investments and Venture Capital highlights the need for catalytic capital from philanthropic and private investors to increase participation from all types of funders.

Key Indicators (Annual)

Best Practices

Interventions which are either not clearly definable as a specific solution, such as incremental improvement of existing common processes, or solutions that have already been implemented by a sufficiently large number of stakeholders such that there is little additional opportunity for them to address food waste that is still happening in the U.S. today.

Improved Communication for Planting Schedules

Technology-enabled coordination between producers to minimize surplus planting and to match future harvest quantities with projected market demand.

Sanitation Practices & Monitoring

Practices and oversight that can reduce contamination, microbial growth, pests, and other food safety concerns, which would otherwise lead to waste and disposal.

Optimized Harvesting Schedules

Coordinated harvest planning that integrates weather patterns, demand-forecasting, and growing timelines to maximize product quality and shelf life.

On-Farm/Near-Farm Processing

Immediate post-harvest processing, such as freezing, drying, jamming, or other, to leverage freshness of products, reduce waste of surplus or damaged goods, and/or minimize transportation costs.

Local Food Systems

Collaborative network in which food is locally produced, processed, distributed, consumed, and recycled to support the health and wellness of the community and environment.

Clear Product Ownership

Defined responsibility for maintaining quality, minimizing losses, and ensuring successful transition of product as it passes hands over the course of the supply chain.

Levers

Financing

- Unlock Returns with For-Profit Internal Capital - These solutions will be unlocked through funding by internal capital from for-profit organizations (Corporate Finance and Spending), as they generate additional revenue opportunities and financial returns for the implementers.

- Public Funding Fulfills Various Capacities - Government Grants can play a key role in financially supporting smaller food organizations and innovators. Additionally, grants can assist with pilot programs to incentivize food businesses in adoption. Program specific government grant funding can aid in the ongoing costs of gleaning organizations.

Annual Investment Needed

Total

$1.5B

Public

Government Grants - $66M

Philanthropic

Non-Government Grants - $68.6M

Impact-First Investments - $67.6M

Private

Venture Capital - $65.4M

Private Equity - $196.2M

Corporate Finance & Spending - $1.08B

Policy

- Expand Farm to Food Bank Programs – [Federal; Legislative] To reduce the financial barrier of farmers donating food, governments can set aside funds to cover the harvesting, processing, packaging, and transportation costs of donating agricultural products to food banks. Federally, Congress could continue the Farm to Food Bank Program (FTFB), authorized for $4 million/year in the 2018 Farm Bill as part of the Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP), increase the funding for the program, and waive the state fund matching requirement. States can look to the Pennsylvania Agricultural Surplus System (PASS) as a model.

- Alternative Tax Credits for Food Donation by Farmers – [Federal, State; Legislative] The existing federal enhanced tax deduction for food donations is not well-suited to farmers and often is not claimed by them, as many farmers operate at low profit margins and do not make enough income to claim a tax deduction. Further, the calculation of the value of the deduction is very onerous for farmers. To incentivize farmers to donate their surplus food and offset some of the costs of donation, Congress could provide an alternative tax credit for farmers instead of the existing enhanced deduction. States can also enact state-level tax credits for food donation, as exist already in about a dozen states.

- Funding for Temperature-Controlled Food Distribution Infrastructure – [Federal, State; Legislative] Lack of cold storage and transportation is a limiting factor for donation of perishables. Congress or state legislatures could provide funding for temperature-controlled food distribution infrastructure (e.g. refrigeration warehouses, temperature-controlled packaging and transportation) to handle additional food donation volume.

- Funding for Further Farm-Level Research – [Federal; Legislative & Regulatory] There is so much still to learn about food loss at the farm level. USDA could conduct studies to quantify and characterize farm-level losses on a semi-regular basis. This could be done through Congress providing funding in the next Farm Bill, or USDA leadership commissioning ERS directly to conduct such studies.

Engagement

- Enable Buyer-Grower Relationships - Rather than regularly changing, if buyers keep staff in positions longer, this will enable stronger buyer-grower relationships that facilitate reciprocity within business, stimulate creative purchasing dynamics, and build trust.

- Share Demand Information- Increased sharing of demand forecasts can help producers plant accordingly and ultimately reduce overproduction.

- Cultural and Behavior Change - Producers should participate in pilot research programs, data collection campaigns, and other collective efforts to improve food utilization best practices, waste reduction strategies, and food management skills.

- Diversify Harvest Partners - Producers should develop and strengthen relationships with alternative harvesting resources, such as gleaning networks or “Pick and Pack Out” programs, to minimize wasted product.

Innovation

- Grower-Buyer Contracts - New grower-buyer contract models are needed to disincentivize overproduction and encourage full utilization of produce on farms, such as is done with whole field purchasing agreements.

- New Approaches to Labor - Farm labor contract models and/or harvest mechanization are needed to address farm labor shortages and the complexities of third-party labor contractors, which can at times lead growers to leave product unharvested.

- Digital Planting Coordination - Digital agriculture technologies are needed to capture, store, and share data in order to support coordination with other growers and inform demand-driven production adjustments, which can lead to less overproduction.

Stakeholder Recommendations:

Here's How You Can Reduce Food Waste

Your Source for Data and Solutions:

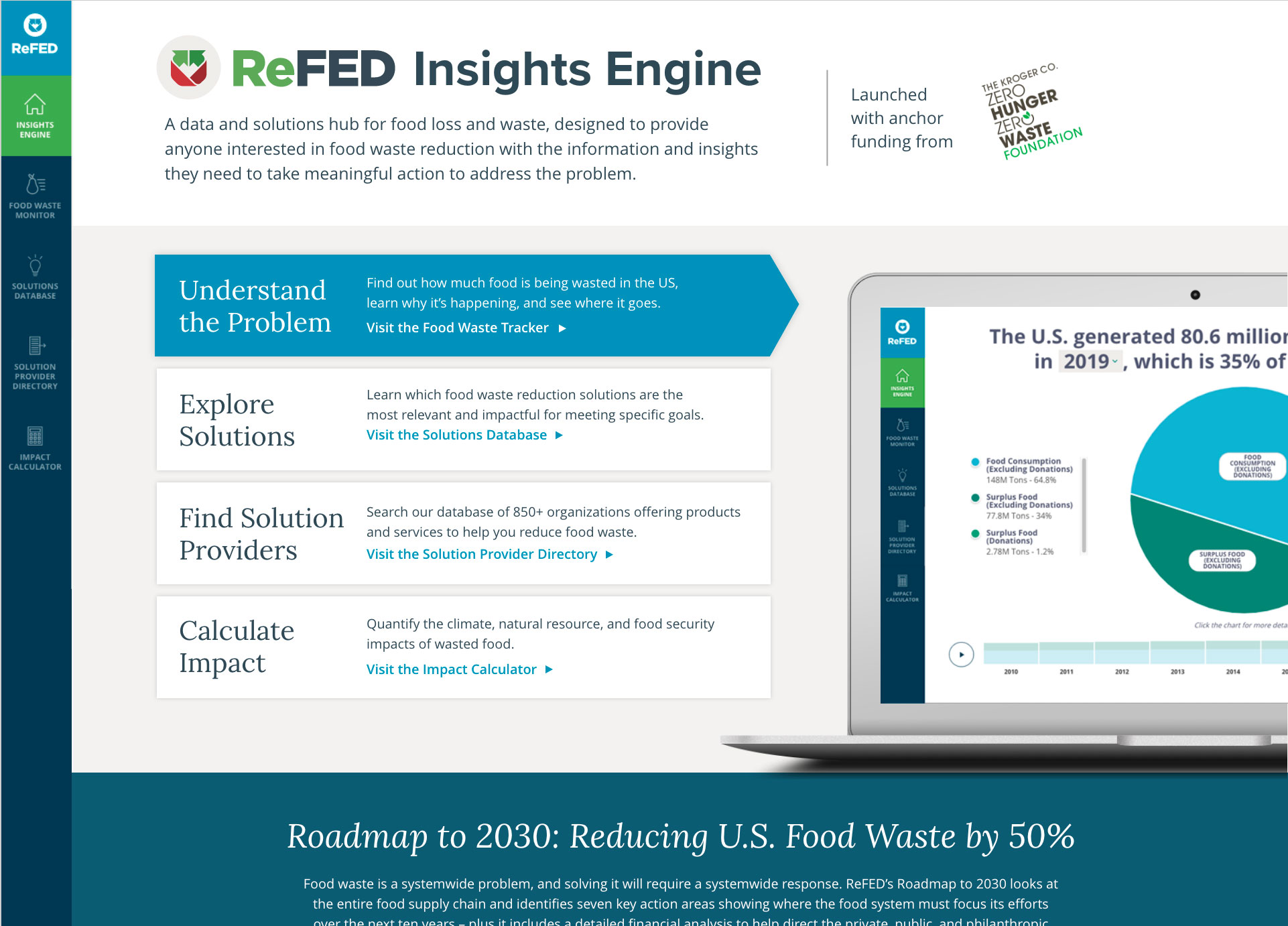

ReFED's Insights Engine

The Insights Engine is an online hub for data and insights about food waste built from dozens of public and proprietary datasets – plus estimates and information from academic studies, industry papers, case studies, and expert interviews – featuring a detailed financial analysis of more than 40 food waste reduction solutions; a directory of organizations ready to partner on food waste reduction initiatives; and more. With more granular data, more extensive analyses, more customized views, and the most up-to-date information, the Insights Engine can provide anyone interested in food waste reduction with the information they need to take meaningful action.

ReFED offers a range of solutions for organizations to advance their own food waste initiatives. Our interactive tools, reports, and strategic solutions can help your team get started.